The gaze – or the male gaze, more specifically – is a discourse that disects how we look at visual representations in film, advertising and art. Coined by feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey in her seminal 1975 essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, Laura argues that persepctives in visual media are often built from the viewpoint of a hetrosexual male, where women are viewed through this lens. The result is that women are often depicted in a sexualised way, where their value is judged based on their appearance. At its heart, women are viewed as objects of male desire. On 21 Nov, curator Lola de la Mata has programmed an evening which explores and challenge this notion of the gaze.

Through another’s eyes

One way of understanding the male gaze in action is to consider you as the viewer. Take for example the painting below:

Professor Andrew Lear notes that the woman in this painting by Francois Gérard (Princess of Talleyrand) shows her looking away from you, the viewer. You are playing an active role in observing, yet she is looking away. Rather than the subject considering the viewer – as art historian John Berger notes – they are considering how the viewer sees them.

Let’s look at this idea when it comes to Sissy Fatigue, a 2019 collaborative film from 4:3 productions featuring in our next event. The short film begins with performer Olivia Norris’ character displayed as a sexualised blonde – the focus isn’t on her face, but her hair and body as she dances flirtatiously in front of a boy.

However, this is quickly subverted once the blonde wig is removed. Olivia morphs into a dominant character, staring directly into the camera without losing eye contact. It makes the viewer feel uncomfortable, prompting us to question – how do we perceive women through fetishised blondeness and stereotypical femininity?

Behind the camera

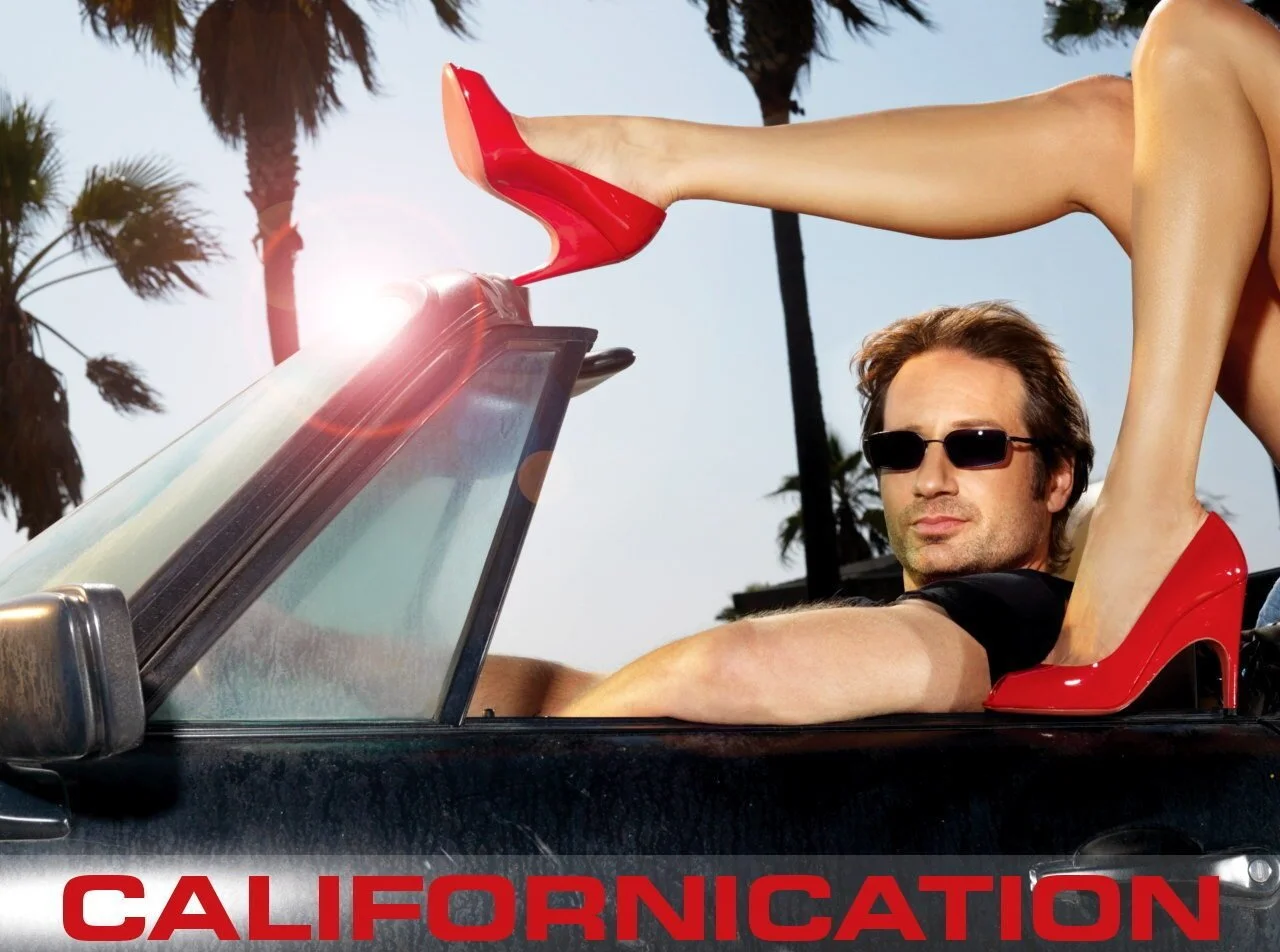

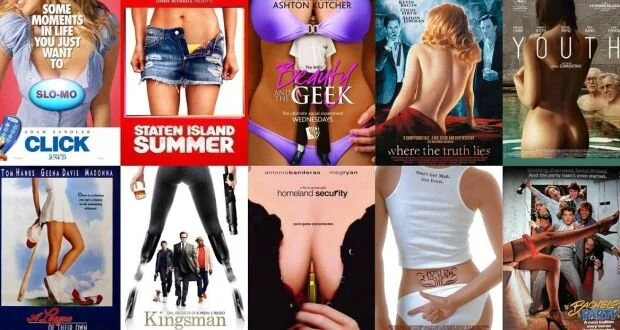

But the concept of the gaze goes much further than just the position of the viewer. Women have often been viewed as submissive characters in film, advertising and visual media in other ways. For example, nearly 50% of contemporary films fail the Bechdel test – a simple evaluation that qualifies the film as having two named female characters who have a conversation about something other than men. In the absence of strong speaking roles and characters which are as nuanced or instrumental to the plot as the male lead, the female roles in film and television thus only become important in relation to the male characters, portraying women as submissive to men. Posters for such films further objectify and trivialise female presence in the media: there’s even a Tumblr account – The Headless Women of Hollywood – which shows the number of posters which obscure the heads and faces of women in favour of more sexualised body imagery.

Exploring these concepts in a visually compelling piece, Q-Hubris is another work featuring on 21 Nov. Created and performed by Riccardo T and Antonio Branco, Q-Hubris addresses the power dynamics in the relationship between idol and worshipper, inviting the audience to consider their objectification of the performers. Through covering a near-naked body in gold leaf, the pair use daring costume and confrontational movement to address the gaze, both upon each other and from the audience. Q-Hubris also takes the concept of the male gaze beyond gender, exploring the power structures of the superior and submissive throughout society: between pop stars and fans, white people and every other race, those who identify as cis/heterosexual and the LGBTQ+ community.

Prominent both historically and in contemporary media, the male gaze inevitably influences the way that not only men, but women perceive and relate to other women and themselves, reinforcing the objectification of women, both in art and in society. See how Lola de la Mata turns the concept of the gaze on it’s head in her discussion about the curatorial process.

Looking back over our recent sell out event at Iklectik.